THE FACE LOOKS STRAIGHT AT ME

AND WITHOUT WORDS

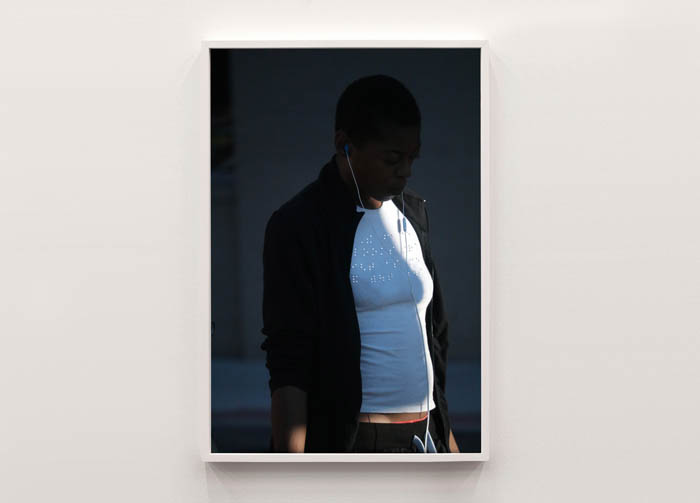

Chromogenic print in artist’s frame

40 x 26,5 cm

2021

THE FACE LOOKS STRAIGHT AT ME

AND WITHOUT WORDS

Chromogenic print in artist’s frame

40 x 26,5 cm

2021

We ourselves speak a language that is foreign. Freud’s formulation, which goes

something like that, stipulates that, regardless of which language we speak, read

or think through, it is foreign.[1]Foreign to whom? To us? To the analyst trying to apprehend it? For ourselves? Unconscious

thoughts, desires, fears and fixations turn our consciousness into a text that

is translated into the language of everyday life. That language is constantly subject

to corrections, deletions, alterations, retakes, additions, and so on. The foreign

elements that overwhelms us, names, dates, rituals, bodies, sculptures, prehistory,

dreams, passions, madness, drugs, and always language, too. It is said that

there are two ways to lose your mind: a) to be absent from the language; b) to

be absently part of it. The

relationship between words and things illustrates our point. It is infused with

a powerful, irresolvable tension: whether the words are a natural part of it,

whether the things are independent, how much they counteract each other,

whether the connection between them was there from the beginning or was

established afterwards. Substitution as a form of madness: the urge to replace

things with words, to symbolically situate the presence of things, in other

words, to define things in their absence. How this difference finally comes to

haunt us. How it threatens to fling gravel in our eyes.[2] Then our eyes

fall out and we can no longer read the text we are writing.

![]()

The situation that the above sentence

describes is the same situation as the one into which it places its non-reader:

an omitted reading, a wordless contemplation. What stands written is:

⠄⠮⠀⠋⠁⠀⠉⠑⠀⠇⠕⠕⠅⠎ ⠌⠗⠁⠊⠣⠞⠀

⠁⠞ ⠍⠑ ⠯ ⠾⠳⠞ ⠃⠺⠎⠲

Read as Braille against the substrate,

the meaning can be deciphered. The raised parts form meaningful characters

while the redundant parts remain flat. To begin with we can think of the

redundant parts in the picture itself. What distinguishes photographs from

other visual media, we could argue, is specifically their redundancy, the

excess of information. In this case, we see a person who stands half turned

away, what goes on beyond that: clothes, individual details, sun and shadows. It

is late in the day, the shadows have lengthened. The body is split into two

parts, the face completely vanishes into the shadow. The arms catch the narrow shaft

of sunlight, they extend down towards what we can assume are plastic bags

weighed down by goods. The person is wearing a headset: the righthand earphone

lead traces a diagonal line through the shadowy section. It ends in a

corresponding lead on the lefthand side, before both continue downwards into a

common cable.

We observed the relief pattern on the

cloth of the jersey. It could be made of a rubber material of the type we so

often see in sportswear. Certain dots ⠄⠮⠀⠋ / ⠇⠕⠕⠅⠎ / ⠊⠣⠞ ⠁⠞ / ⠯ ⠾⠳⠞ ⠃⠺ shine out clearly, while others ⠁⠉⠑ / ⠌⠗⠁/ ⠍⠑ / ⠎⠲ can only be made out from the shadows

that they cast on the clothing. It is a tactile statement whose meaning is not

immediately accessible to us when we view the picture on the wall. The

inability to read the text is what interests us here. There is a kind of radical

uncertainty or helplessness inscribed into this very incapacity that takes our

thoughts to the unconscious. We do not really know whether the message has any

recipients, whether it is trying to say something to anyone. We do not know

whether the other one wants something. That is why we try in advance to reflect

that uncertainty. When Freud’s successors talk about the unconscious, it is

specifically in the sense of a kind of broken communication:

Precisely as an enigma, the symptom, so

to speak, announces its dissolution through interpretation: the aim of

psychoanalysis is to re-establish the broken network of communication by

allowing the patient to verbalize the meaning of [her/]his symptom: through

this verbalization, the symptom is automatically dissolved.[4]

The symptom arises when the words are lacking, where the meaning has been excluded from the cycle of discourse. It constitutes a kind of continuation of the broken communication, but in encoded form. The goal of the analysis is in effect to restore communication through enabling the analysand to decipher the code, that is to say, to articulate the meaning of their symptom so that it can be dissolved. The continuity of the subject’s history is restored retroactively by creating meaning in the apparently meaningless. In a sense the symptom does not exist without its recipient: in analysis it is always addressed to the analyst, like a targeted invitation to decode its hidden meaning. In our case the code is self-reflexive to the extent that it explicitly communicates its own impossibility: the recipient of the message remains mute and wordless. In what sense is the script impossible more specifically? There are two linguistic modalities of impossibility, the first of which deals with linguistic (un)consciousness. For reading to come about, understanding is required so that something constitutes language, in this case an array of dots on an article of clothing. Its units of meaning can easily be mistaken for decorative additions: beads, sequins, rubber textures, quite simply objects among many others, which they also in a sense are. In this first stage we encounter the words in a reified form, unaware that they bear meaning. The words take off from within the language, yet they do not reach the reader, but are only accessible specifically as objects. Does this not say something about words in general? Words can be read, but they can also be looked at: they are disguised objects. Words denote objects, but now themselves get object status.

(The fantasy of reification, of the word-object, could be extended to include a moment of mutual transformation. A person becomes an object through words, not as a result of sexism or linguistic objectification, but due to a profound affinity between the word and the person themself. To see a word and feel how it moves inside you. To feel yourself inside the word, how the word reads you. If you persist long enough with the word-object, you becomeit. You do not grasp the message, so instead you are turned into it.)

The inability to conceptualize the

message as something other than an object recalls the magic realm before language, before our cognition of

meaning through language. We should, however, bear in mind that objects are language, objects have syntax and can be read in many different

ways. The very fact that we conceptualize something as an object indicates a

linguistic dimension. The notion of a pre-linguistic set of objects overlooks

the fact that “object” is a linguistic event. As Wittgenstein explains: “What

reason have we for calling ‘S’ the sign for a sensation? For ‘sensation’ is a

word of our common language […] and it would not help either to say that it

need not be a sensation; that when he writes ‘S,’ he has something – and that

is all that can be said. ‘Has’ and ‘something’ also belong to our common

language […]”[5]For Wittgenstein, we might add, it is only within language that signs signify. Hence,

signification cannot explain language. This is another way of saying that there

is no metalanguage. Every syllable is a dot that conceals the movement ofits

origin. Every dot is a movement. Every movement conceals where it is carried

out: