CSS Smooth Text Color Transition

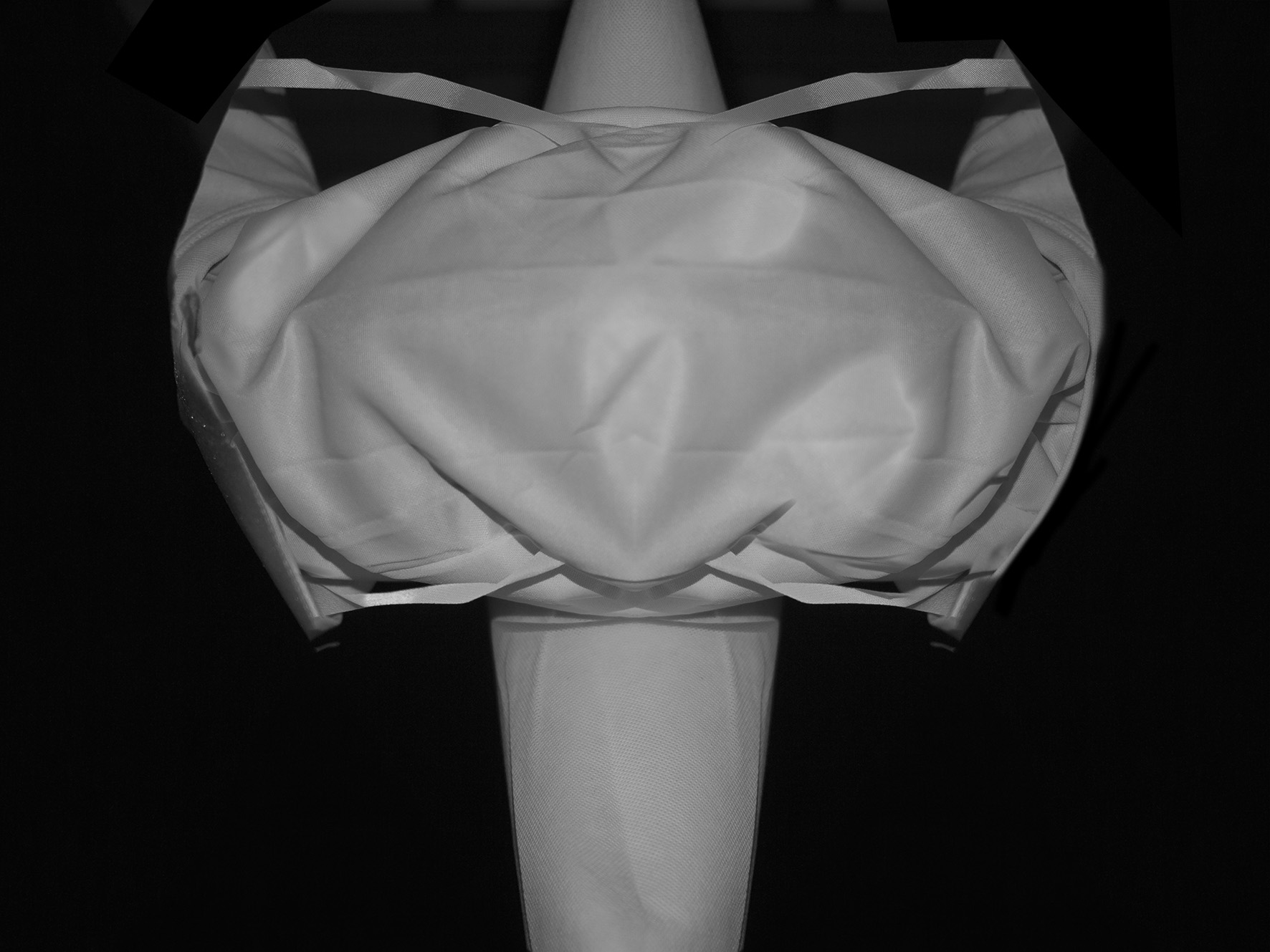

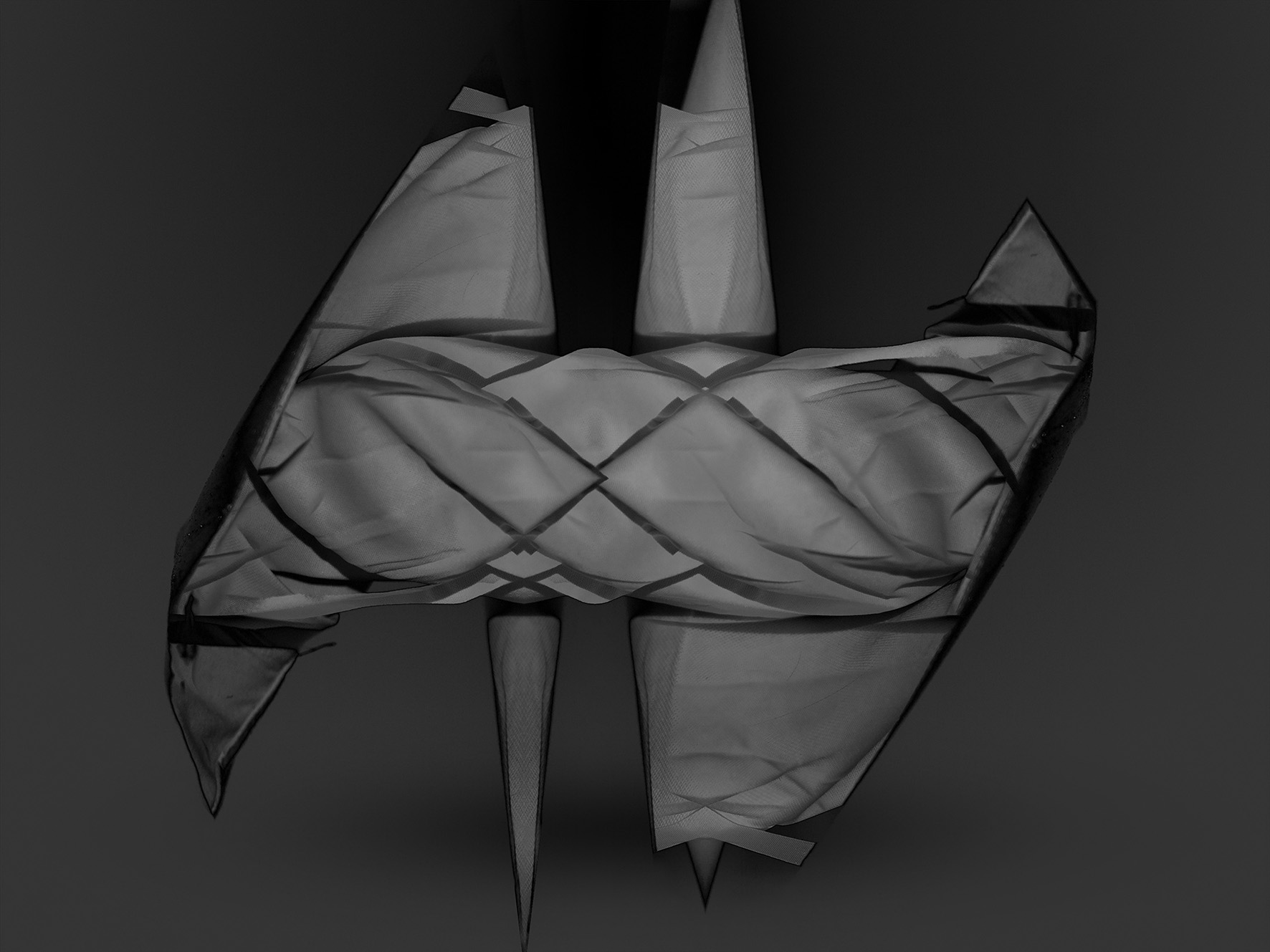

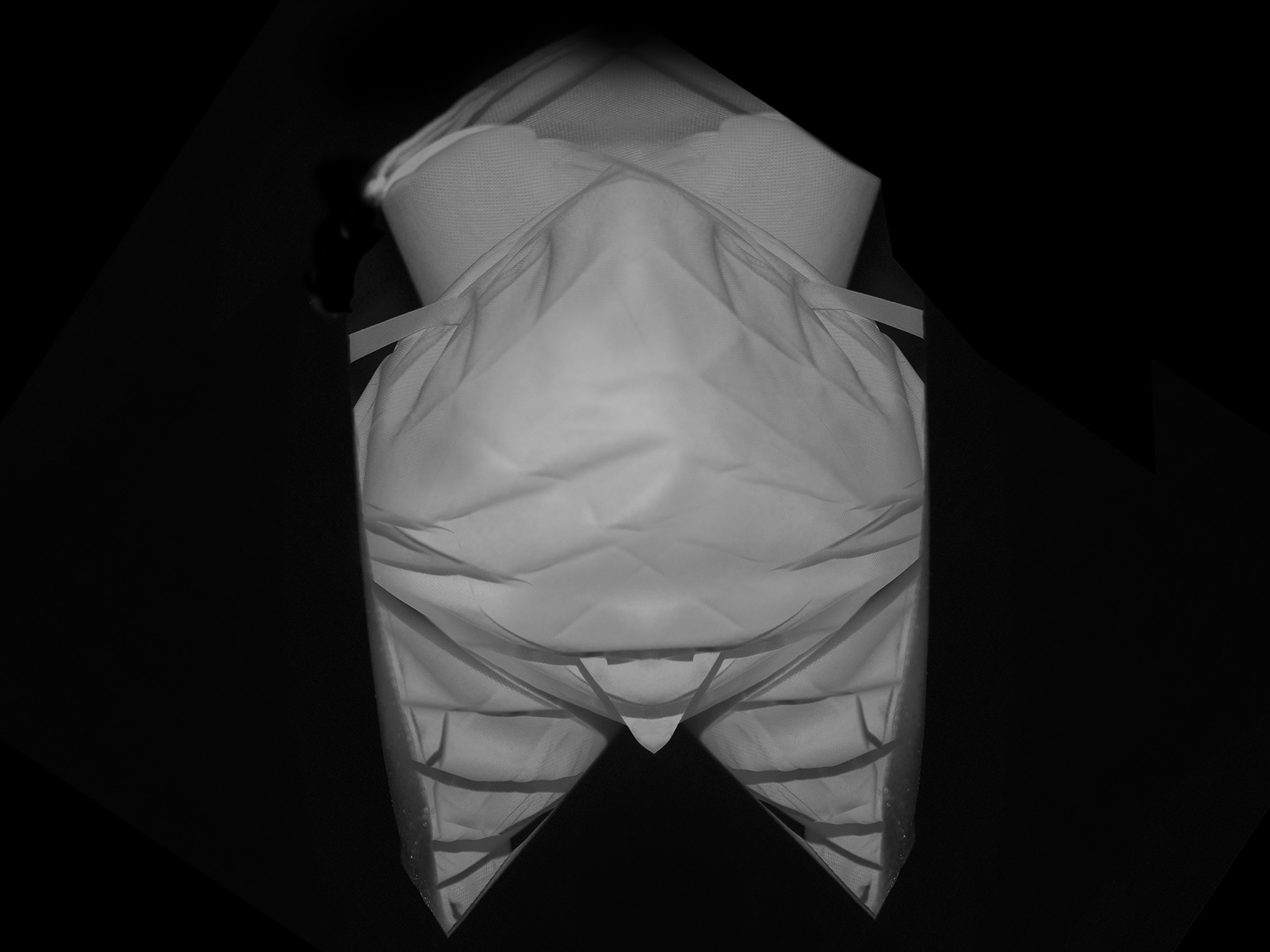

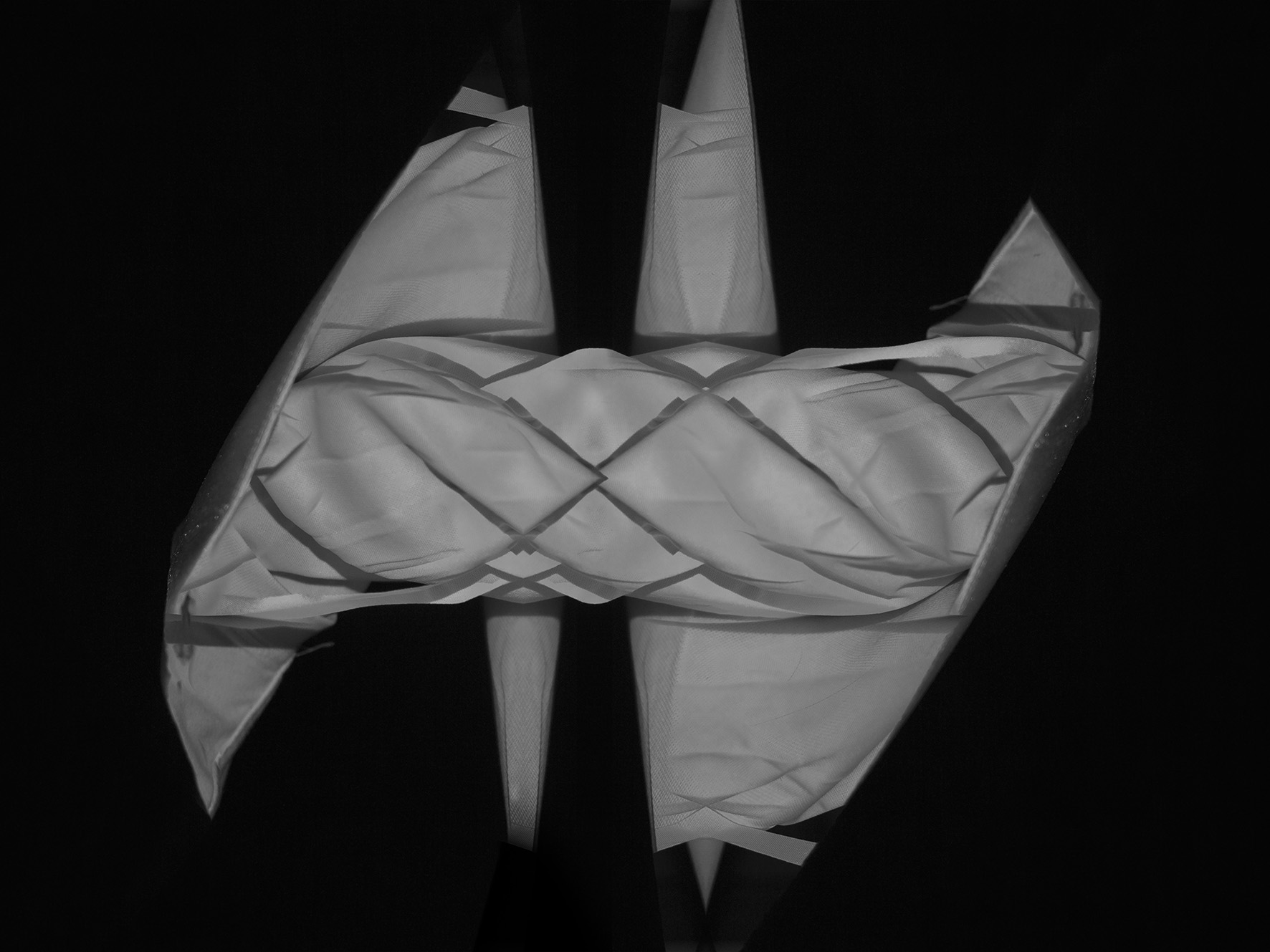

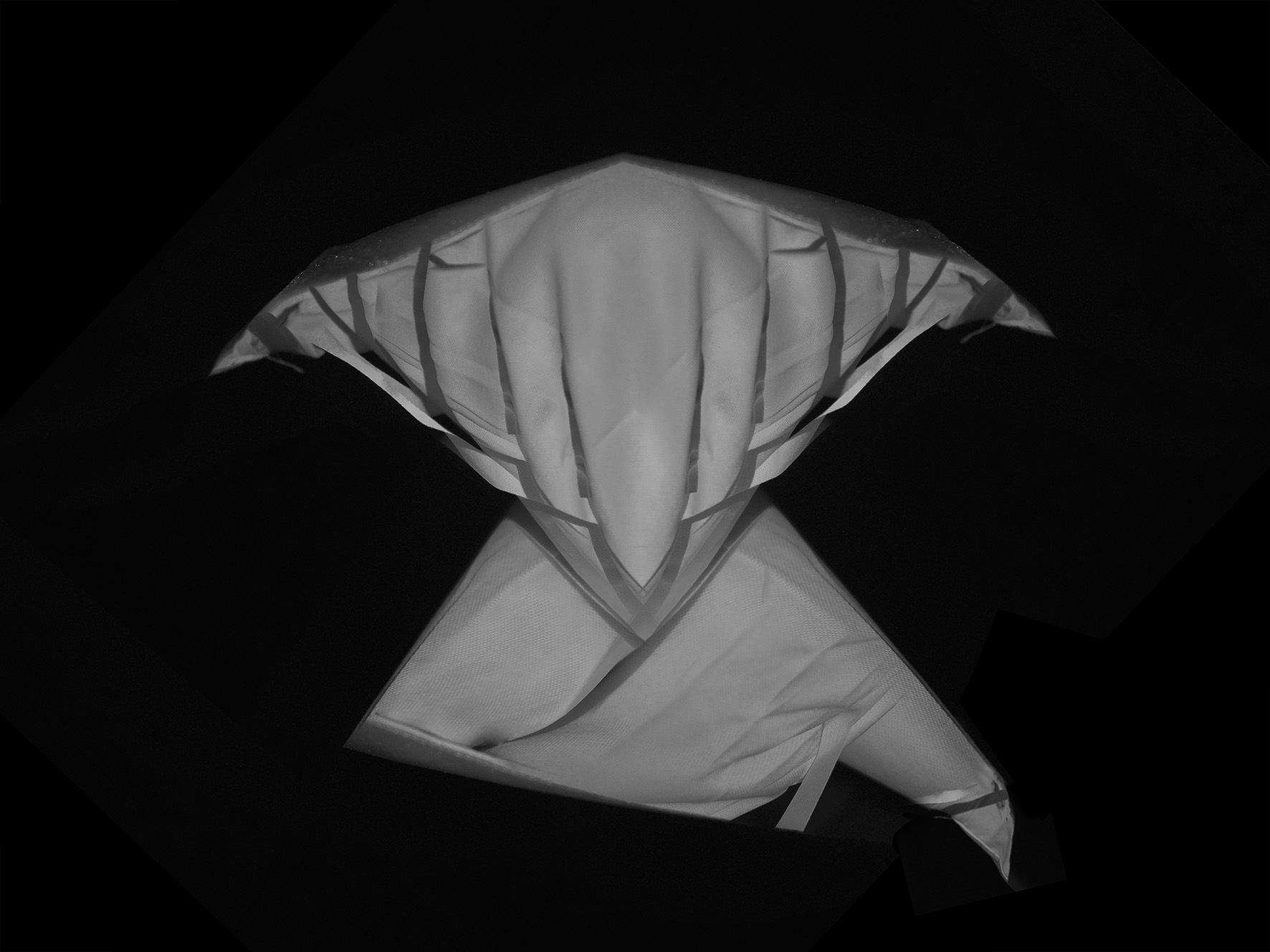

CORNETTE (UNTITLED I—XII)

Chromogenic prints

65 x 48,5 cm

each

2021

What to wear,

what not to wear. Right now, I want to be wearing a cornette. That is a kind of

folding headgear. More specifically I want to be in its folded form. It is a

form that allows something to be revealed and concealed at the same time. I

believe this is possible without losing control. In fact, it is all about

control. If control is a variable that regulates the flow of visibility, we operate

with multiple controls. The behaviour of those controls also includes their own

visibility. The behaviours of controls sharing a form often correlate: some

controls are always hidden while other controls are visible; some controls are

repositioned while other controls are shown; some controls are both shown and

hidden at the same time.

Wimples. They all look alike on white walls. But not all

walls are the same. The wimples are the walls and change with them. They

are their own changeable walls.[1]

Seam. Or what is in the seam. Fold it with your eyes closed, stitch a seam

along each fold, like the inside of someone’s thoughts. Must you know the

answer to everything?[2]

Fold. Nothing but cloth, folded in layers. The significance of the fold.

That which is folded in and that which unfolds. That which is revealed and that

which stays concealed. Now we see everything at the same time. Now we see

nothing.

Sign. Extrapolate that the sign reveals/conceals itself in a form that is oracular rather than ocular. Heraclitus

says: “The lord whose oracle is in Delphi neither indicates clearly nor

conceals but gives a sign.”[3]

[1] The historical

interweaving of the cornette with white walls is traced out in Elizabeth Kuhn’sThe Habit: A History of the Clothing of Catholic Nuns (New York: Image,

2007), 110.

[2] One of the meanings of the veil is encapsulated in a formulation by Paul

Celan: “Half image, half veil.” This enigmatic phrase bordering on the

elliptical comes from one of the poet’s few prose pieces, Conversations in the Mountains. What is fascinating about the work

is not least the story of its origin. It was written in August 1959, shortly

after a missed meeting with a nameless person on a mountain road. (Cf. James K.

Lyon, Paul Celan and Martin Heidegger: an unresolved conversation, 1951-1970(Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006), 163.) The meeting that

did not take place is significant. Life is filled with missed or impossible

meetings. You only have to take the subway to witness some of them. The meeting

that does not take place triggers a chain of possible outcomes of that meeting,

which in turn gives rise to intensities such as longing, imagination and

wonderment. Missing someone you have never even met. There are, however,

different ways of not meeting, which the pandemic situation has inventively

demonstrated. (Someone aptly described Zoom meetings as a contemporary form of

séance. Someone is trying to make contact. Are you there? We cannot hear you.

Do you hear us?)

If we return to Celan’s work we get into a conversation

between two cousins who: "have no eyes, alas. Or more exactly: they have,

even they have eyes, but with a veil hanging in front of them, no, not in

front, behind them, a moveable veil." (here and in what follows: Paul

Celan, "Conversations in the Mountain”, in Collected Prose (Manchester: Carcanet, 2003), 22—23.) Everything they see is mediated by the

veil, it winds "itself around the image and begets a child, half image,

half veil." Neither words nor pictures suffice for the absolute alienation

that is the world. In other words, the veil is a trope for nothing less than

the unsayable.

[3] Heraclitus, Fragments (London: Penguin Books, 2003), 190.